It is certainly not news that India has a rapidly expanding presence in New Space, but it is still surprising how long the nation’s remarkably robust space industry has continued to fly largely under the radar and out of view of the western portion of our industry.

My introduction to the Indian space community was born of necessity. In 2014, Russia invaded Crimea, and in doing so, earned a stern rebuke from the U.S. Government (USG). Among other measures, Washington responded by rescinding export licenses needed to transport U.S. satellites to Russia for launch on Soyuz and Dnepr rockets.

Consequently, the launch portion of Spaceflight Industries, which I headed at the time, was prevented from shipping customer satellites to Yasny. As it happened, on the last possible day we could ship the satellites and still make launch, we miraculously received our export approval, one of the last licenses granted to a U.S. company until a long time thereafter.

On the sleepless night that preceded the approval, I vowed that we would not find ourselves in such a predicament again. Thus began our long journey to discovering and appreciating the incredibly overlooked and undervalued Indian space community.

At that point ten years ago, rideshare on Indian launches, though not unheard of in the U.S., were certainly not mainstream. Rideshare was, at that time, still primarily the province of university cubesat programs. Commercial rideshare was a small business in the U.S., with few small, reasonably priced, launch vehicles. Most companies offering mid and large launch vehicles were not excited by the idea of a multitude of small satellites hitching a ride on their vehicle, because an untimely secondary payload failure could mean the loss of the rocket, their primary payload, their reputation, and their insurance rates.

While the smallsat satellite capacity shortage has still not been completely addressed, suffice to say that from 2012 to 2022, as the situation was especially dire.

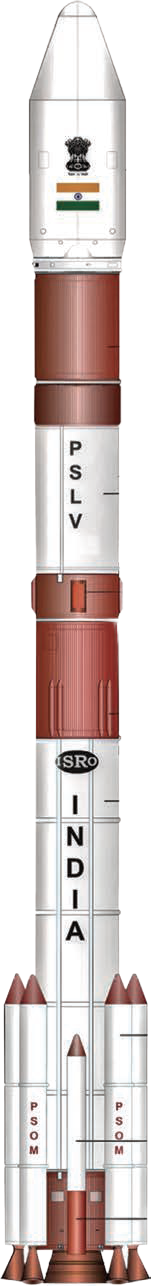

India’s workhorse launch vehicle, the mid-size Polar Satellite Launch Vehicle (PSLV), was (and remains) highly reliable, and a few foreign smallsat operators were buying entire PSLV launches at reasonable prices. Unfortunately, India had not yet signed the Commercial Space Launch Agreement (CLSA), which was a condition of opening access to U.S. commercial interests.

A friend of mine had recently helped a U.S. operator navigate State Department restrictions and obtain a waiver to buy a full PSLV, and he was kind enough to provide me with the name of the head of Antrix, which was, at that point, the commercial arm of the Indian Space Agency (ISRO).

After exchanging emails, Mr. Radhakrishnan and I met at the International Astronautical Congress in Toronto, Canada. Little was I to know that Radha was to become a tremendous business ally, but also a close friend. Incredibly humble and soft-spoken, he asked about Spaceflight, the sort of customers we had, our level of experience and our plans to obtain approval to launch on PSLVs. He invited me to Bangalore, India, to sort out the details once we had our approvals.

At that point, the prospects of purchasing secondary capacity from Antrix seemed real enough to warrant a call to Spaceflight’s International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR) counsel, who was, in fact, the very same attorney who had assisted in obtaining the waiver necessary for the initial U.S. small satellite launch from India.

As this undertaking was quite fact-sensitive, our counsel arranged a trip to Washington D.C. to meet with the officials in the State Department’s Directorate of Defense Trade Controls that oversee ITAR licensing.

After explaining the shortage of launches from the U.S. (and other approved nations), and the consequences of such to the fledgling small satellite industry posed by the prospect of zero Russian or Indian launches, we received approval to book launches from India — provided there were no U.S. launches to a roughly equivalent orbit within six months of the target Indian launch,

and additionally that we adhered to the compliance requirements set forth in a technology transfer control plan facilitating the involvement of a Defense Technology Security Administration monitor in key meetings and on the ground at the launch site.

At that point, it was finally time to head to Bangalore! Equipped with a long list of customer spacecraft that required a home, I met first with Radha, who took the time to talk through our capacity needs and then, as a complete surprise, the Chairman of ISRO.

That trip ultimately led to Spaceflight booking a total of 175 spacecraft over 15 PSLV missions. As with all things in the space industry, there was a steep learning curve with both high and lows. Overall, we found PSLVs to be a super reliable launch vehicle, with the people of Antrix, and then NewSpace India Limited (NSIL), cooperative, hardworking, and committed to providing a favorable outcome for Spaceflight and its customers.

Did they work in the same way as U.S. launch companies? No. Do they have a stellar safety record, envied by almost all in our industry? Yes.

Until SpaceX initiated the second wave of price reductions under its Transporter program, Indian launches were the most reasonably priced launches in the world (apart from Chinese and, infrequently, Russian launches).

The main drawbacks were periodic issues with schedule reliability (which were caused by delays in the readiness of Indian national satellites, which controlled launch schedules as the primary customer), but that of course is a hazard of booking rideshare as a secondary payload on any launch vehicle. With experience, we were able to more reliably predict which launches would have longer delays, based on the track record of specific Indian national satellite programs.

As time went on, we encountered situations where component inventory demands (such as separation systems or cubesat deployers) prompted us to inquire whether NSIL had these components available, or whether, as part of a launch, they could engineer parts they had identified as necessary to enable necessary deployment angles.

The NSIL team was adept at providing these components on schedule and at a reasonable price. We even seriously considered partnering with them for satellite and orbital transfer vehicle manufacturing, even though we ultimately did not advance those discussions.

Just as NASA did, the Indian government saw the value of partnering with the private sector to foster economic growth. Over the past several decades, the Indian space program has created a strong internal engineering organization and has worked to transfer technologies, in-part, using a government contracting model.

By 2017, their aerospace industrial base counted more than 500 suppliers of various components. However, the private sector still played a supporting role, while the government continued to dominate the space sector. In the late 2010s, Indian startups emerged with their own proposals and concepts to develop various satellite technologies and rockets. In 2020, Indian National Space Promotion and Authorisation Centre (INSPACe) was established to incubate technology into private firms.

In August of 2018, the U.S. Commerce Department placed India in Country Group A:5, thereby granting authorization for exports to India under License Exception Strategic Trade Authorization (STA) under the Export Administration Regulations (EAR). India was only the 37th country to join Country Group A:5, alongside the UK, Canada, European Union member states and other close U.S. allies.

This reclassification was part of a broader effort to recognize India’s strategic trade relationship with the United States and to facilitate the export of certain controlled items to India. The change aimed to simplify and enhance trade between the two c untries while ensuring that export controls were appropriately managed.

This has led to an easing of the export of non-ITAR spacecraft for launch to India — a huge change from 2014!

As recently as April of 2024, an amendment to India’s Foreign Exchange Management (Non-debt Instruments) Rules was proposed which would liberalize entry routes for potential investors in Indian space companies. It allows up to 74 percent foreign investment in satellite manufacturing and operation, satellite data products and ground segment and user segment are allowed under automatic route, and up to 49 percent is allowed for the Creation of Spaceports, Launch Vehicles and associated systems or subsystems

My personal story, though perhaps unique at the time, is certainly no longer an outlier. We at Spaceflight considered ourselves fortunate to team up with the brilliant men and women leading the charge on one of most exciting frontiers for the NewSpace economy.

I look forward to watching NSIL’s new launch vehicle, the SSLV, grow its record of success and I am as enthusiastic as ever about India’s future in space and their expanding contributions to the sector.

Curt Blake

Author Curt Blake, Senior Columnist to SatNews Publishers, is Senior Of Counsel at Wilson Sonsini Goodrich & Rosati. He is an attorney and senior executive with more than 25 years of experience leading organizations in high- growth industries—and more than 10 years as the CEO of Spaceflight, Inc.— at the forefront of the New Space revolution.

Curt has extensive expertise in strategic planning, financial analysis, legal strategy, M&A, and space commercialization, with deep knowledge about the unique challenges of New Space growth and the roadmap to success in the that ecosystem.

The views expressed in this article reflect those of the author himself and do not necessarily reflect the views of his employer and its clients.