At any given moment, about 750 million people with mobile phones in their pockets are outside the range of the world’s terrestrial cell towers.

This lack of a connection is usually just a minor annoyance, but often it has major social and economic consequences, and sometimes is even a matter of life or death. Fishermen and farmers, hikers and hunters, and many others die every day because they cannot use their mobile phones to ask for help when they need it the most.

People living in or near cities often don’t think much about mobile phone connectivity until they happen to travel to an area with limited or no coverage. In fact, only about 25 percent of the world’s land mass has coverage from terrestrial phone towers. The other 75 percent is comprised of mountains, forests, deserts and wide-open spaces in between that are too underpopulated to justify the cost of constructing a cell tower.

Astronaut photo taken from ISS of a Lynk cell tower in space. Photo is courtesy of NASA.

Mobile network operators in the U.S. spend about $25,000 per square mile of coverage area to build a cell phone tower and another $17,000 a year per square mile to operate and maintain it. If the new revenue from customers living in the cell tower’s coverage area isn’t at least $20,000 per square mile, the tower probably won’t get built.

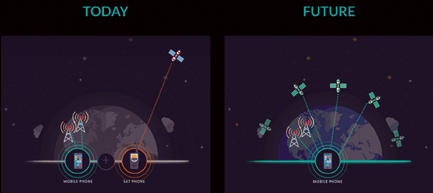

Lynk solves this economic problem by filling in all the “mobile black spots” not with land-based towers, but rather from space. Cell phone connectivity to every corner of the planet, on land and at sea, will be extended with “cell towers in the sky” that provide a safety net to people in the most remote locations. Relief agencies and first responders will have a reliable means of communication even when terrestrial networks go down in major cities following natural and man-made disasters.

Lynk is building small spacecraft that appear as ordinary cell towers to standard mobile phones. To achieve this, Lynk has solved a series of key technical problems.

For example, a standard cell phone connected to a terrestrial tower generally has a range limited to around 35 kilometers (21 miles) if the line-of-sight is not interrupted by hills, buildings, or foliage. The phone signal can travel further, but the reception range is artificially limited by the highly accurate time frames of the cell phone protocol.

To get the phone to connect to a satellite flying 500 kilometers (310 miles) overhead, Lynk’s software at the satellite overcomes the built-in time-frame distance limit built into standard phone protocols.

Another innovation allows standard phones and Lynk’s spacecraft to transmit and receive on the same terrestrial radio frequencies already in the phone. No change to the radio transceiver chip in the phone is required. Lynk calls this innovation in spectrum sharing “Complimentary

Space Component.”

Lynk’s cell network in the sky compliments the terrestrial towers that primarily use this spectrum, without harmful interference. This is the exact opposite of “ancillary terrestrial component,” which is when satellite spectrum is shared by terrestrial systems.

All of these innovations, when combined, will deliver a reliable and constant service to the end-customer. People can stay connected everywhere, with the phone in their pocket as this service does not require users on the ground to buy an expensive terminal or device — or any software — to connect. The off-the-shelf cell phone in their pocket is the terminal. This means the marginal cost of the hardware to use this service is zero.

The requirement to use the very small antenna already in the phone creates some limitations. The speed of this service over LTE is 180 kbps. But 180 kbps is infinitely faster than 0 kbps. Having Lynk’s service could save people’s lives. If someone uses Lynk, they get “peace of mind.” For many, that will be good enough.

Lynk does not compete with companies such Intelsat, SES, Viasat, OneWeb or SpaceX. It is in a completely different category and Lynk’s success will expand the business of all these named firms and more.

A brand-new category of services called “satellite fronthaul” has been created by Lynk. It provides direct-to-phone (“fronthaul”) connectivity in areas where terrestrial towers and WiFi are uneconomical. By doing so, Lynk increases the need for satellite cellular-backhaul and satellite WiFi-backhaul.

Lynk can’t directly compete with high throughput systems such as ViaSat, OneWeb or SpaceX’s StarLink, which place a broadband antenna on the roof of a home, school or business. The WiFi they provide with these larger antennas will be a couple orders of magnitude faster than

Lynk’s service.

However, when someone walks out of that building, they will not take their ground antenna with them, but they will take their phone. Lynk will be their best friend when they are out of range of WiFi and cell towers. For many of the 2.5 billion people in the world who currently do not own a mobile phone, it’s because they live or work in an area with no mobile coverage.

After Lynk builds a cellular network in space, affordable coverage will be available everywhere. The service will be affordable even in developing countries. For example, in sub-Saharan Africa, being connected requires buying a refurbished feature phone, which is available for ~$2. Analysis suggests up to a billion more people could and would buy a mobile phone if they had affordable coverage where they live and work.

Lynk represents a major gateway to new mobile phone usage in the world. It will give many of the last 2.5 billion people without a phone a compelling reason to get one. Once they start using a phone, these new subscribers will want even faster speeds than Lynk can provide. The increased density of mobile subscribers in remote areas will drive demand for new cell towers and WiFi hotspots that only satellite can serve.

The business case will close for more satellite cellular-backhaul and WiFi-backhaul deals in remote areas. Lynk’s success will be good news for these traditional categories of satellite services.

A rising tide lifts all boats. Lynk estimates that, over the long term, extending mobile wireless service everywhere could generate as much as $400 billion in additional annual revenue to the telecommunications industry. The increased customer adoption of mobile phones around the world will benefit satellite and terrestrial companies.

The artificial divide between satellites and terrestrial systems is about to end. For mobile network operators, Lynk will fill their coverage gaps and give them an opportunity to add new customers and better serve existing ones. For traditional satellite operators, it will increase the demand for cellular backhaul and WiFi backhaul in remote locations that are not well served by fiber

or microwave.

Lynk’s vision is that nobody again should die because they have a phone in their pocket and are not connected.

Never again should a fisherman die because they did not get the warning of a hurricane headed their way.

Never again should a farmer die because he or she rolled the tractor in the back field and could not call for help.

Never again should emergency responders be unconnected after the earthquake, tornado or power outage takes the mobile network down.

Lynk is looking forward to collaborating with the rest of the satellite industry to make the vision of everywhere everyone connectivity into a reality.

www.lynk.world

Charles Miller is co-founder and CEO of Lynk. He is a serial space entrepreneur with 30 years’ experience in the space industry. Charles has been the founder or co-founder of multiple private ventures and organizations. He is a national leader in the creation and development of public-private partnerships in commercial space to serve public needs.

One of Charles’ previous startups is NanoRacks, which has delivered more than 700 payloads to space and is the current world leader in smallsat launches.

Charles served as NASA’s Senior Advisor for Commercial Space from 2009-2012 where he advised NASA leadership on commercial public private partnerships. At NASA, he managed USG teams that developed strategies for commercial development of reusable launch vehicles, on-orbit satellite servicing, orbital debris removal, microgravity applications, lunar development, space communications, and space solar power. Charles’ clients have included NASA, DARPA, the USAF, and many private commercial space firms.