The Washington DC satellite show saw panel after panel talking about the prospects for LEO constellations.

NSR’s Activity List

The past month or two has seen this picture become even more complex, with a clutch of highly optimistic plans being unveiled for a series of LEO constellations which their proposers hope will satisfy—and help to create—a growing demand for broadband bandwidth around the planet.

The likes of Greg Wyler and his ambitious OneWeb scheme is designed to emulate and out-perform the O3b series of MEO satellites he helped co-found and he is typical of this new generation of satellite entrepreneurs. Elon Musk, already globally famous for his PayPal success, his Tesla electric car, and quite spectacular SpaceX ‘rockets to Mars and everywhere else’ aims is yet another. LeoSat is another beast in the making, promising terabytes of capacity and tapping into anticipated demand. Throw in self-seeking publicists such as Virgin Galactic’s Sir Richard Branson and you win guaranteed column inches of press coverage.

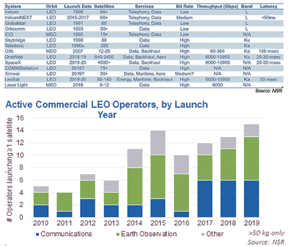

Northern Sky Research (NSR), in a report published last month, speculated that the combined result—if all of these constellation placements were successful—would mean anything up to 5,000 LEO satellites being launched in the next decade. By any measure, and even if they do not all launch, this still means a true quantum leap of extra satellite bandwidth coming into play. This equates to tens of terabits of capacity and a hoped for reduction in the cost/GB tumbling down, all to the consumers‘ benefit.

Not yet answered is exactly how all of this hardware is going to get into orbit. Even with today’s quite sophisticated orbital injectors, their positioning is still going to require a gigantic thrust of rocketry to achieve a business case.

Then there’s the financing—while there’s plenty of cash around for well-structured satellite projects, perhaps the extremely deep pockets of a Qualcomm or Google will be required to see if these schemes can actually fly.

However, what if they do all crack the meaningful challenges of mass-producing satellites (at a rate of two-a-day, if Thales Alenia is correct) and actually line up for launch? NSR is blunt in its assessment and I cannot disagree with it. NSR says some serious questions are starting to emerge.

“How does an industry build and launch ~5,000 satellites, even if they are much smaller than the traditional GEO COMSATS? With the same 17 to 20 active launchers, averaging the same 75 to 80 combined launches per year to GEO and LEO, launching all constellations in a two to five year window seems near impossible. NSR estimates that if all constellations do go ahead as planned, we are looking at capacity of the order of 20 to 30 terabits coming online in the next decade, which is orders of magnitude higher than the 2.5 terabits of GEO/MEO HTS capacity that NSR expected by 2023.”

Where will all of the demand for this new capacity be derived from, remembering all the while that the telcos and fiber-layers are not exactly idle in expanding their networks and penetration? Will an over-capacity ‘bubble’ drive some of these schemes into bankruptcy?

NSR added, “Even if the industry remains divided on whether all this capacity constitutes a “bubble,” it remains feasible that 20 to 30 terabits of capacity could be launched by 2020. Hypothetically, if all this capacity were available today and sold at rates of $500/Mbps (equivalent of $1,500 to $2,000 per MHz in Ku-band at 1:3 or 1:4 Bits per Hz modulation and coding) it would mean revenues of the order of $15-$20 billion, which is 10 percent of the entire satellite industry’s revenues as per the 2014 SIA report.

Now one must factor in that only a portion of this capacity can be truly “commercialized” and only 30 to 40 percent of it is over land mass, not to mention unique landing rights in each country that make selling this capacity a rather tough problem to solve. And cost effective antenna technology required on the ground is far from reality anytime soon, which may be a larger problem that launching massive volumes of capacity into orbit.”

Do not forget that the established satellite players are also not resting on their laurels. Almost every major operator is aggressively expanding their ‘High Throughput’ fleets. Inmarsat, Intelsat, SES and Eutelsat are all typical of the breed and continue to add to the amount of capacity on offer.

It would be easy to report on the challenges that these new entrants face. Top of the list has to be financing, especially with the less than stellar performance histories of 14-15 years ago, when planned constellation after constellation failed and cost backers millions.

But even assuming the funding can be sourced, then there’s the already mentioned ‘build and launch’ physical challenges to be engineered and achieved. Perhaps Elon Musk can create another revolution in thinking how satellites can be built—and he has a solid record of achieving what he promises. But as many as 4,000 satellites takes a bit of development, and testing, and planning and launching and solving the numerous terrestrial problems and then finding a market!

One highly respected observer calls some of the schemes “preposterous” and funded by organizations and individuals who have “more money than good sense.” He reminds the industry that most of the schemes proposed about 20 years ago were also under-funded and over-estimated in terms of the ROI, and he doubts whether even the new SpaceX constellation could see the cost of building and launching drop by 99 percent.

There’s another expensive factor to be considered. Today’s major satellite operators have generations of expertise in managing their fleets, with skilled engineers and technicians. These skills will need to be generated almost over-night by these new constellations. Ground installations will not be cheap, and even O3b doesn’t interface with the public (but stays strictly B2B).

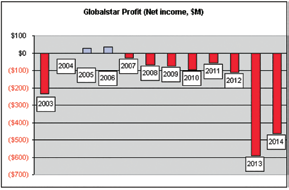

Perhaps Google and the others will create a whole new business sector serving the public and interfacing with the satellites. Perhaps. But this is not going to be an overnight happening. Moreover, the proven history of systems such as Iridium and Globalstar is not good. They’ve both been through Chapter 11 and have not set the world alight since their rescue and re-launch.

Iridium’s constellation is kept afloat by support from the U.S. government, and, despite making regular profits for the past five years (net profits of $50 to $70m over the past three years), the company is, nevertheless, obligated to pay back a massive $384 million each year for the next 10 years and also needed to fund its ‘next generation’ fleet.

Whether we have another 2000-type ‘bubble,’ or whether the new breed of satellite entrepreneurs have timed their investment decisions well, only time will tell. This place in space is going to be watched closely!

Wyler’s OneWeb Plans Explained

Greg Wyler, the original thinker behind O3b’s mission to capture the “other 3 billion,” used the Washington show to explain his new mission as head of OneWeb and his plan to serve the other three billion via his OneWorld strategy, with a constellation of 648 active LEO satellites (at 1200 kms), plus another 250 in construction (for replacements/redundancy) and at a cost of about $400,000 each.

Wyler, in a special presentation, demonstrated how a Rockwell Collins-designed snazzy rooftop all-in-one antenna could serve a village or an even larger community from a central point.

OneWeb has attracted funding and participation from Qualcomm and Sir Richard Branson and currently is talking to five potential suppliers (including three European and two American actors). A decision could emerge shortly as to the successful bidder. Thales said it would build an all-new facility if it won its bid. Wyler wants the first launches to occur in 2017.

Airbus Defence & Space, OHB and Thales Alenia Space are the European trio, while Space System/Loral and Lockheed Martin are the U.S. pair. The pre-bidders will not have to wait too long, as it emerged during the show that a decision could be made quickly.

The intention is to then form a j-v with the winning bidder and build a dedicated factory to build satellites at an unprecedented rate. Thales, for example, said the company would need to manage two a day in order to have an initial working constellation into space by 2017, all in order to secure and ‘bring into use’ the ITU-authorized frequencies. The bulk of the satellites would launch in 2018.

Thales Alenia’s New ‘Ready To Fly’ Models

Much of the talk at the DC show revolved around new demands on satellite builders, with operators expressing extremely firm views that they needed shorter delivery times, less expensive satellites, more functionality, and a great deal of fresh thinking for the supply side of the industry.

Jean-Loïc Galle, CEO at Thales Alenia Space (TAS), stressed that his company was actively addressing all of these elements, but admitted that the changes could be dramatic over the next few years. “But, we will be at the forefront of these changes.”

Indeed, he opened his presentation by revealing that last year’s commercial sales totaled five major satellites, and “we would not have won any of those contracts had we not worked hard on our cost structure, trimming about 10 percent from those costs and looking to save a similar amount this year. We have also looked hard at our product lines and also the classic Spacebus platform.”

He explained that TAS saw the market for commercial satellites falling into three clearly defined groups: The first was for HTS, where the satellite would be complex but the cost per Gigabit would have to be lower. The second group included what he described as “Low Cost/Short Schedule, low CapEx but being extremely agile for operators.”

The third group were global-reach satellites, with very low latency, and a large number of new services. “This means the new constellations,” he agreed, and this topic alone was a major focus at the show.

He said the global market for Group 1 and 2 satellites was probably about 20 craft in a year, but also cautioned that many people did not fully appreciate the high degree of complexity of a major HTS satellites. He also stated that TAS was well placed to compete effectively in supplying sub-24 months delivery dates on the supply of (largely) pre-configured craft. He added that TAS would be employing more robots (and co-robots where a human was involved) to trim the time taken on certain tasks, and thereby keep costs down and delivery dates shorter.

“Our customers are pushing us very hard for standardization and we are increasingly looking at these automated processes, as in the car industry, for improvements. And in some cases, we are targeting 18 to 20 months for delivery.”

Some of these developments are revolutionary and include using 3D Printing technologies to speed some production processes on complex components. One specific 3D Printing task was ‘super accurate’ and delivered a 50 percent saving in mass and costs. Another task saw robots inserting the aluminum honeycomb elements on a satellite’s bus and achieving super accuracy as well as a reduction of a (human-based) time from around a week of labor to just about six hours.

The StratoBus, image courtesy of Thales Alenia Space

He added these lessons were being applied to all of its manufacturing units, and while he spoke optimistically of winning business from the new breed of constellation owners and developers, he was under no illusion of the challenges and difficulties ahead. Separately, Greg Wyler had talked about 900 or so satellites at a cost of $400,000 per unit.

Galle said this was achievable but also meant turning the OneWeb mini-sats out at a rate of two per day. “We have to examine how to do this. How will this affect our own internal supply systems, as well as those of our outside contractors? These are just the first steps.”

Galle also spoke extensively about the TAS-developed and patented ‘StratoBus’ flying drone/balloon, which would ‘fly’ at 20 kms and stay in a geo-orbit for about a year, despite the craft’s low speed. It would weigh some five tons, carry a 200 kg. payload, and be ready for use next year. The StratoBus would then return to Earth, be refueled and be returned to orbit—this craft could be ready to fly in 2020.

The ‘Big Four’ Chat To 9000

The focus was—as ever—on reducing the costs of launch vehicles, and, in particular, in reducing the time of building and assembling satellites. The general consensus was that 30 to 36 months for actual manufacture was far too long a period of time.

The Big Four opening session (David McGlade, CEO of Intelsat; Dan Goldberg, CEO of Telesat; Michel de Rosen, CEO of Eutelsat; and, for the first time on the panel, Karim Michel Sabbagh, CEO of SES) spent perhaps more time than was justifiable in discussing the prospects for the raft of new LEO constellations, especially as none are likely to make an impact for some time to come.

The headline grabbing multi-satellite projects coming from SpaceX/Elon Musk, and Google—and with the most recent big-name investor being Richard Branson and Virgin Galactic—were generally welcomed but there was much speculation—and sly comment—as to which of the many competing blue-sky projects would ever see the light of day.

SES’ Sabbagh, with his old boss watching from the second row, could hardly deny he was in favor of constellations, given that SES is a 46 percent shareholder in O3b. The expectations are that SES will likely consolidate that ownership in the next year or so. O3b is already raising fresh cash to expand the constellation beyond the existing eight fully working (plus four less than perfect) orbiting craft.

“The most interesting growth opportunities still lie ahead of us. We’re here to truly democratize satellite connectivity. Our satellites cover 99 percent of the world’s population, but we don’t serve 99 percent of the population—why not?” Sabbagh asked.

For McGlade, the event was his swan song. He will retire next month, but he was also happy to address the wider market opportunities in ‘smart’ devices and second screens, saying, “the proliferation of devices that consumers are consuming content on, not just in the U.S., Europe and some parts of Asia, but seeing programming proliferate through new devices in all markets more cost effectively.” He also cautioned wisely about getting “too overheated” in worrying about the new LEO competition until everyone’s plans were a little clearer. McGlade admitted that the satellite industry was in a period of innovation that has accelerated rapidly in the last five years.

De Rosen highlighted that operators have been in a constant innovation cycle, citing the example of Eutelsat’s Smart LNB “which will be a great tool for interactive non-linear TV, but also for broadband in emerging markets.”

The panel responded to questions about several new important technology developments which could fundamentally revolutionize the way satellites are ordered and built. These technological developments could, depending on the industry’s willingness to embrace change, completely transform the way the satellite industry operates.

New software programmable payloads could mean an end to the two- to three-year wait for a satellite to be built following an order from an operator. Satellite manufacturing should become much more of an assembly line, with customization of payloads being done as a pre-launch adjustment of more standardized ‘off the shelf’ spacecraft. Several industry leaders likened the paradigm change to having satellites become similar to mass produced Fords, rather than each spacecraft being an expensive handcrafted Ferrari, or as a French rocket builder described on the next day, very Haute Couture, when they needed to be ‘Ready to Wear’ (actually, Prêt à Porter, said in heavily accented French!).

Michel De Rosen highlighted the advantage Eutelsat had taken in this area with the announcement of its advanced Quantum satellite. However, and not for the first time, he delivered a very public warning to the industry’s big names. While he did not mention Arianespace (or Proton, or any of the satellite builders by name), it was clear he wanted to see modern business practices start to enter the sector. Fresh from the textbook launch of one of his SatMex (Eutelsat Americas) all-electric satellites by SpaceX, he told the 9,000 delegates that “SpaceX, their energy, is now shaking the entire launcher industry and forcing the other players to become much more competitive themselves.”

The other big development for the satellite industry in the coming years is the emergence of HTS, which promise much more power while delivering dramatically lower cost per bit. The combination of HTS and a totally new way of much more speedily commissioning, building, launching and lighting up satellites all spell good news for broadcasters—lower cost and faster time to market.

The upcoming WRC-15 meeting of spectrum regulators in November, and the threat from cellular operators and some governments to confiscate C-band spectrum, was also much discussed. The big satellite operators have gone to great lengths to demonstrate to the ITU why any kind of spectrum sharing will devastate not only many TV businesses, but also humanitarian aid operations worldwide and will have a deleterious effect on many developing economies.

David McGlade, CEO of Intelsat.

However, the mobile lobby stands accused by the satellite players as being guilty of a dirty tricks campaign, with de Rosen unhesitatingly alleging that the mobile providers are blatantly lying in order to win the day. The mobile lobby just recently issued a press release, said de Rosen, claiming that Arab states had declared in unison that they do not need to preserve C-band as satellite-only, and have effectively given these frequencies to mobile. “This is simply not true,” said de Rosen.

Indeed, when pushed on the whole question of sharing their C-band assets, the CEO’s of SES, Intelsat and Eutelsat, all gave a firm ‘No’ when asked whether sharing was likely. Dan Goldberg, not for the first time on the panel, uttered a logical ‘Maybe’ as an outcome of WRC-15.

Michel de Rosen, CEO of Eutelsat

While TV remains a key revenue source for The Big Four—some 70 percent of SES’ revenues, for instance—the leading operators offered much optimism in regard to their newer business concentrations in maritime, aviation, oil & gas and other B2B and government communications services, as well as bringing broadband to the underserved masses. Only Dan Goldberg name-checked Ultra-HD as the main reason to be excited about satellites’ immediate future.

Dan Goldberg, CEO, Telesat.

However, there was one over-riding message—the Big Four view the industry as being in a healthy state and firmly rejected the suggestion that there was an over-capacity problem looming.

Senior Contributor Chris Forrester is a well-known broadcasting journalist and industry consultant. He reports on all aspects of broadcasting with special emphasis on content, the business of television and emerging applications. He founded Rapid TV News and has edited Interspace and its successor, Inside Satellite TV since 1996. He also files for Advanced-Television.com. In November of 1998, Chris was appointed an Associate (professor) of the prestigious Adham Center for Television Journalism, part of the American University in Cairo (AUC), in recognition of his extensive coverage of the Arab media market.