In 2014, one era of European space activity is drawing to a close, with a new era on the horizon. The future of the flagship Ariane launch vehicle is driving this transition; it is Europe’s single most critical space decision, upon which myriad developments hinge—from Europe’s share of the commercial launch market, to next-generation satellite designs, to multinational civil space collaboration activities.

The European launch sector, challenged to become more cost-competitive, is consolidating—and likely upending geographically dispersed vehicle production patterns in the process. Yet a less obvious countervailing trend is also at work: a proliferation of national and even sub-national space initiatives that has been subtly reshaping the European space landscape since the turn of the century.

These two trends, consolidation and dispersion, are interacting in nuanced ways; while they may offset each other in particular countries or regions, they are not necessarily in opposition. Rather, they reflect a European market that is mature from a technological perspective, but more variegated and less predictable from a commercial or government stakeholder standpoint. The dynamic interplay between these two trends means that enterprises working in the European space sector will need to update their business models, take this much broader range of actors and market forces into account, and capitalize on the new opportunities they enable.

A Fateful Moment

In December, the European Space Agency (ESA) Ministerial Council will meet in Luxembourg, where it is expected to commit to a roadmap for the next-generation Ariane vehicle. Development of the Ariane 5 Mid-Life Evolution (ME), approved at the 2012 ESA Ministerial Council, is already underway. Designed by Airbus Defence and Space (formerly Astrium), the Ariane 5ME will yield a 20 percent increase over current payload capacity, lifting up to 11 metric tonnes to geosynchronous transfer orbit (GTO), and thereby replacing the Ariane 5 ECA and ES versions by 2018. The question before this year’s ESA Ministerial Council is whether, and to what extent, to fund continued development of the Ariane 5ME in balance with (or opposed to) an alternative configuration, the Ariane 6, which would differ markedly from the Ariane 5 legacy design.

Whatever ESA’s decision, it will turn the page from one chapter of European space activity to the next. Versions of the Ariane 5 have been in operation since 1996. The Ariane 5 ECA configuration (see the artistic rendition to the right, courtesy of ESA), able to deploy two geosynchronous (GEO) satellites in one launch, has flown since 2002. Despite its reputation for quality and reliability, however, the Ariane 5, like all vehicles, has faced price competition from SpaceX’s Falcon 9. In response, European planners are considering next-generation designs to maintain or expand market share while increasing cost-competitiveness.

European Launch Sector Consolidation

This challenge is already prompting significant realignment in the European space industry. In June, Airbus and Safran—the two largest industry shareholders in Arianespace, owning a combined 39 percent of that company—agreed to a 50-50 joint venture. The partnership seeks to integrate the launch system design capabilities of Airbus with the propulsion expertise of Safran.

The goal is to simplify organization within the Ariane production process, and create an integrated entity responsible for development through commercialization. Together, Airbus, Safran, and Arianespace seek to optimize their cost structures, both for continued development of the Ariane 5ME and future design and production of the Ariane 6.

To that end, the Airbus-Safran joint venture has already proposed two new concepts for the Ariane 6 vehicle: the Ariane 6.1, a heavier-lift version capable of deploying up to 8.5 metric tonnes to GTO (enough to carry either one massive telecommunications satellite or two smaller ones); and the smaller Ariane 6.2, designed mainly to place Earth observation spacecraft into low Earth orbit (LEO), replacing Arianespace’s current usage of Russian Soyuz rockets for this purpose.

While the Airbus-Safran joint venture will create new efficiencies, fundamental reductions in European launch development costs will require significant changes to Europe’s longstanding policy of geographic return, or juste retour, whereby industrial contracts are distributed based on proportional investment by European member countries in the institution awarding those contracts. The impact of geographic return on ESA has been to spread space production among multiple countries, which shares the wealth but can also increase costs. Changes to this approach would likely result in consolidation of vehicle production at sites in France and Germany.

While disruptive, the pressure to increase European cost competitiveness appears to be creating political room for this change. “I have given industry total carte blanche on this,” ESA Director General Jean-Jacques Dordain said in a press briefing on January 17, 2014. “I want them to tell me the best way of moving forward, with no constraints.”

On July 30, Airbus CEO Tom Enders echoed those sentiments. “The management is tasked with a clear mission: to improve competitiveness of the future European launcher business,” stated Enders. “This objective is without alternative for me—either we fundamentally drive change in this sector, or we risk becoming irrelevant very soon.”

Geographic Dispersion In European Space Activity

Notwithstanding this industrial consolidation, any reductions in the geographic expanse of European launch vehicle supply lines may be tempered by an alternate trend: growth in national space initiatives among individual European countries.

The UK Civil Aviation Authority’s unveiling at the 2014 Farnborough Air Show of eight potential sites for a British commercial spaceport offered the latest illustration of this trend. This commercial spaceport initiative is one element of the broader Space Growth Action Plan unveiled in April by the UK Space Agency. The plan names space as one of Britain’s “8 Great Technologies,” and aims to position the UK to capture 10 percent of the global space market by 2030, increasing the contribution of space activity to the British economy from an estimated £9 billion today to £40 billion by 2030.

Although investments in the Space Growth Action Plan are largely channeled through the UK’s ESA budget contribution—noteworthy given British euro-scepticism—its focus is squarely on fostering space business within the UK through de-regulation and “smart” investment in core space industries, such as launch and Earth observation.

While Britain has been active in space for decades, its creation of a dedicated space agency in 2010 was designed to raise the profile of space within the UK government, showcase links between space investment and technological advancement, and orient human capital development toward a high-skills economic cluster.

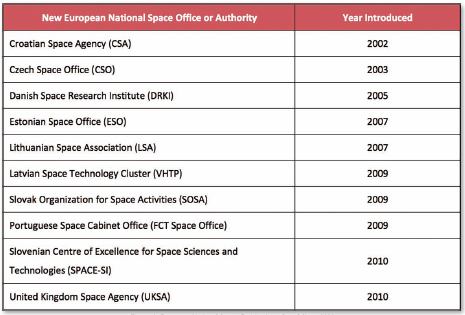

The UK Space Agency is only the most recent example of European countries investing in their own national space initiatives for similar reasons. At least 10 such entities have been created across Europe since 2000, several of them in Central and Eastern Europe. Beyond national authorities, certain jurisdictions within European countries have also created localized space initiatives.

In Belgium, for instance, the Walloon region has created Skywin, which has funded more than $100 million in aerospace projects and regional export promotion. Walloon is also one of 27 member regions of the Network of European Regions Using Space Technologies (NEREUS), a multinational group whose mission is to assist in the development of regional European space clusters. Against this backdrop, the July rollout of the UK commercial spaceport initiative might be viewed as an exclamation mark on a European space trend that has been gathering momentum for the past 15 years. (Please see Figure 1 above.)

This multiplication of national and regional initiatives also reflects some tension in European space governance. The majority of European national space spending still flows through ESA, reflecting a broadly shared consensus that individual European countries achieve more in space through pooling their resources for collective action. However, European nations are also hedging their bets: investing in their own national capabilities, or re-evaluating ESA space spending through the prism of their domestic interests.

For instance, although the UK Space Growth Action Plan highlights increased British funding of ESA, its clear priority is leveraging that investment to enhance the British national space economy. This suggests a desire to set the ESA agenda as a founding member, and perhaps also to preserve ESA as the primary locus of European space decision-making, rather than ceding influence to Brussels institutions, notably the European Commission.

Figure 1. European National Space Entities Introduced Since 2000

Conversely, six of the ten European national space authorities created since 2000—Croatia, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Slovakia, and Slovenia—are members of the EU, but not of ESA (although several aspire to membership as “ESA cooperating states”). Rather than waiting for ESA to grant membership, or bowing to the priorities of France, Germany, Italy, and the UK, the largest ESA contributors, these small countries are formulating their own space futures. All are eager to join ESA and support its initiatives, but each is developing a distinctly national space approach as well, with emphasis on public-private partnerships, capital attraction, and workforce development.

While some of these governance questions, along with the broader relationship between ESA and the EU, are agenda items at the 2014 ESA Ministerial Meeting, their resolution will be an ongoing process. Meanwhile, European national and regional space initiatives appear poised to proceed, and possibly increase, even as ESA continues as the primary driver of European space activity.

The Reshaping Of The European Space Landscape

While the future of the Ariane launch vehicle is of decisive importance, consequential transitions are already underway throughout the European space sector, irrespective of ESA’s decision. Europe’s space industry is simultaneously consolidating and shrinking its geographic base to cut costs while also undergoing a geographic proliferation of space activity at national and regional levels.

The interplay between these dual forces of consolidation and dispersion is creating a more dynamic but less predictable—and multiplying—set of market actors and forces. Companies will need to tailor their medium- and long-term strategies to changes in longstanding launch vehicle production and supply chain models, as well as a diversification of European space activity among a larger patchwork of actors. While the multinational ESA space model is well-established, the multiplication and depth of national space initiatives—and the opportunities they present—have not yet been fully grasped by businesses in Europe or internationally.

In this moment of change for European space activity, it is important for companies to understand the implications of the looming Ariane decision on the horizon as well as the business possibilities presented by the cumulative effect of the many decentralized national and regional decisions that are combining to reshape the European space landscape in 2014.

For additional information regarding AVASCENT, please visit http://avascent.com/

About the author

David Vaccaro specializes in international initiatives at Avascent’s Space Practice. Avascent is a strategy and management consulting firm serving clients in government-driven industries.