The timing could hardly have been worse for anyone trying to monitor ship congestion at Chinese ports, a topic of critical importance to understanding today’s global economy.

One manifestation of this year’s supply chain chaos has been the record number of ships anchored outside the world’s busiest ports, a function of COVID-related factors leading to increased wait times to load and offload cargoes.

Port logistics have never been under such intense scrutiny, and then this happened:

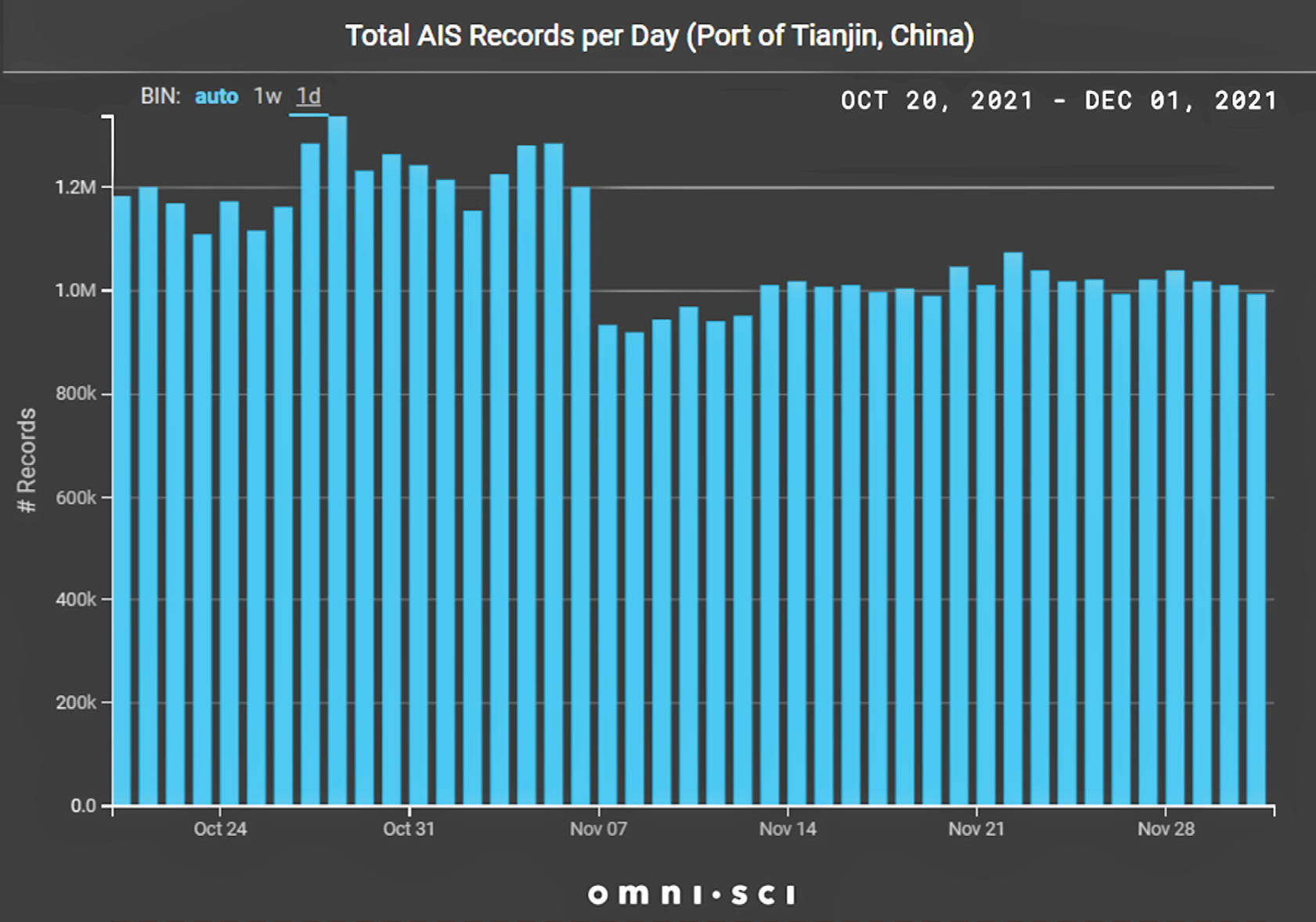

1. The number of Automatic Identification System (AIS) signals from ships in Chinese waters declined late October and then dropped precipitously in November.

2. Ships around Chinese ports basically disappeared from the screens of popular websites that use AIS signals to track the whereabouts of the world’s commercial fleet.

3. A critical information stream that a wide range of professionals (e.g., shippers, economists, traders, bankers) rely on practically dried up overnight.

Fortunately, other methods exist to detect ships, helping to fill in the gaps left by the missing China’s terrestrial AIS data blackout.

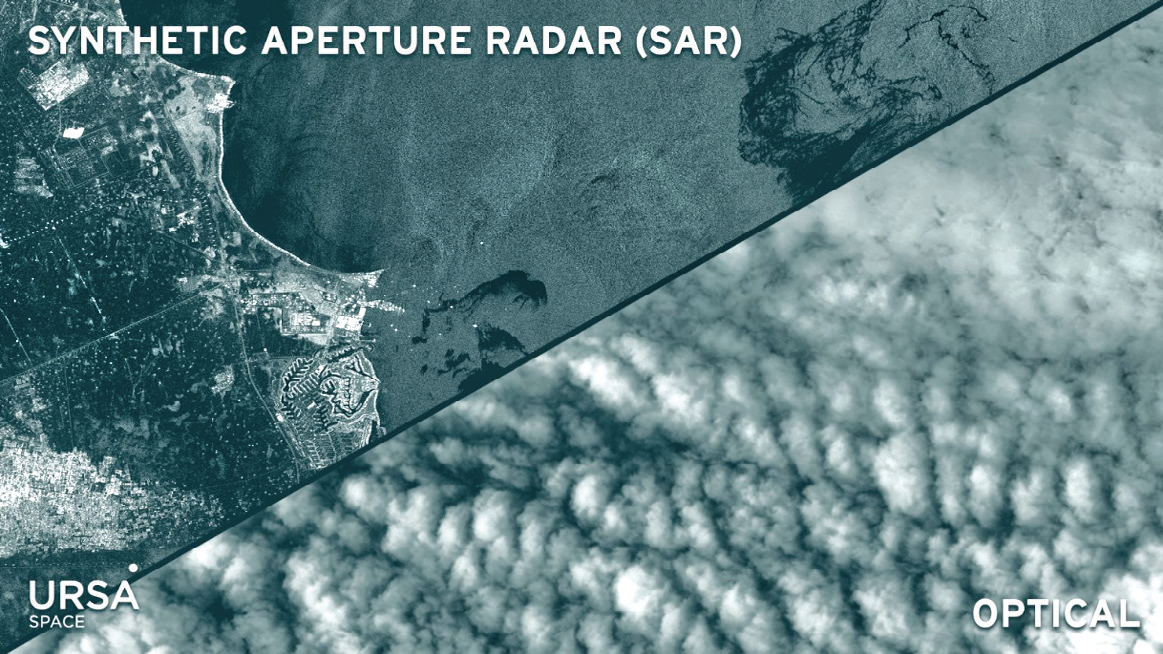

At the top of the list is synthetic aperture radar (SAR).

Unlike optical satellite imaging, which is similar to taking a picture with a camera and relies on sunlight, a SAR imaging system produces its own energy source that interacts with the Earth’s surface.

A portion of the signals are reflected back to the instrument, in patterns that carry rich information about the features encountered, easily allowing for the detection of a vessel, such as a container ship or oil tanker.

The only catch here is the complexity of actually processing and analyzing SAR data, which happens to be Ursa Space’s expertise. SAR’s other advantages include its ability to:

• Work day or night, with no sun illumination requirements, and in any weather condition.

• Capture complex elements, such as speed and direction of movement.

• Gather information over large swaths at lower resolution or very detailed, high resolution images over smaller areas.

• Combine with other types of data in unique ways. In this video, Ursa Space and HawkEye360 fused SAR + RF signals to monitor the South China Sea.

In the maritime context, one of SAR’s many real- world applications, much of the focus has been on countering illegal fishing or sanctions violations, in which ship captains turn off AIS transponders in an attempt to evade detection.

The current situation along China’s coast is similar insofar as ships there have also gone “dark” (i.e., no AIS signal), though the reason why vessels have gone dark is different (details below).

Regardless, we can apply the same tried-and-true SAR technique to locate ships that have seemingly “vanished” from China’s coast.

To demonstrate this point, let’s look at the Port of Tianjin, 110 km. outside Beijing.

The graphic, above right, shows the number of unique AIS messages per day around the Port of Tianjin dropped by approximately 20% in early November versus last October.

On this basis alone, you might wrongly conclude that traffic around Tianjin slowed in November.

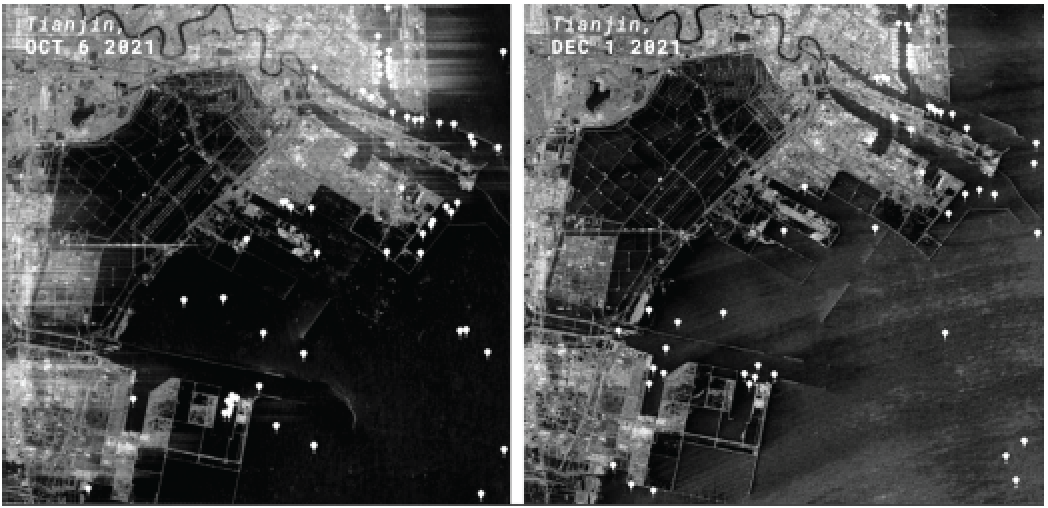

Take a look at the two SAR images above, collected over Tianjin on October 6 and December 1. We applied algorithms to detect vessels and found both dates had roughly the same number.

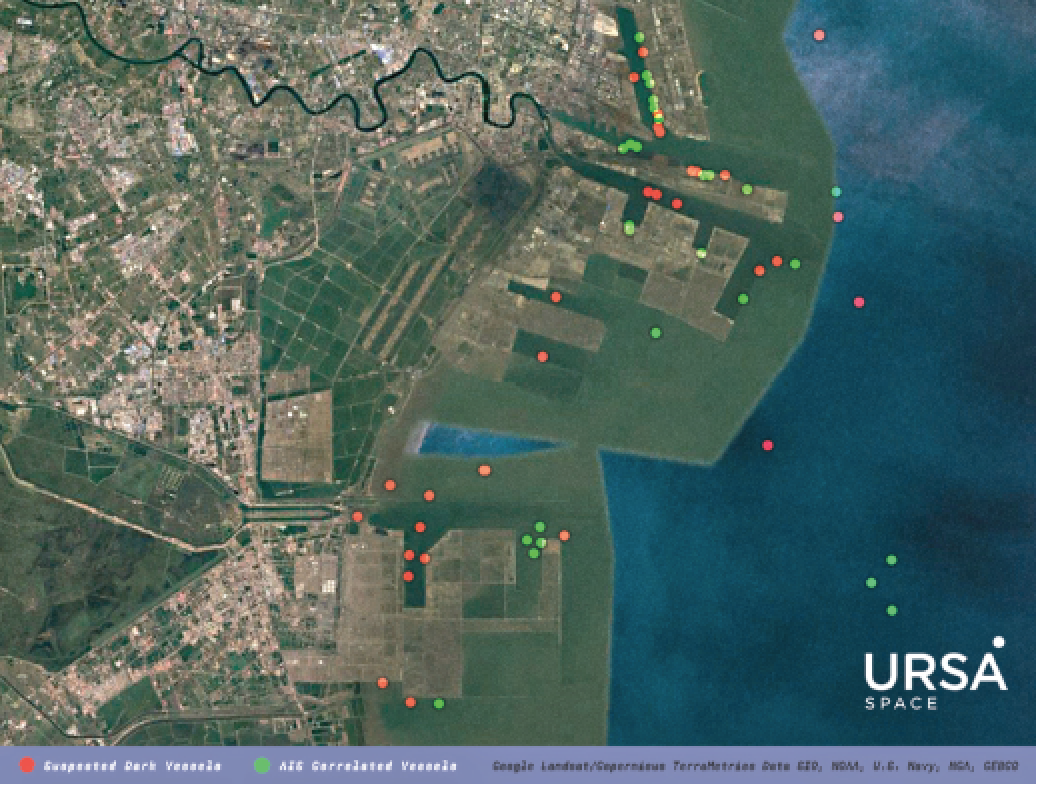

Next, we correlated the ship detections in the December 1 image with AIS signals. Any ship without a corresponding AIS signal was considered a “suspected dark vessel.”

The image below shows the breakdown between suspected dark vessels and AIS-correlated vessels.

What’s causing the AIS data outages? By all accounts, ship captains have kept on their transponders. In that sense, the circumstances are different from illegal fishing or sanctions violations.

To understand what’s happening, let’s delve a little further into how AIS works. AIS transponders onboard ships transmit information to receivers located onshore every 30 to 45 seconds. There are an estimated 402 terrestrial AIS stations in China, dotted along the entire coastline and inland rivers. Vessel tracking services (e.g., MarineTraffic, VesselsValue) own the ground receivers, but Chinese providers manage the transmission of that data to them.

According to news reports, these providers stopped relaying the AIS data to the tracking services for fear of incurring penalties under a new law, effective November 1, that requires receiving approval from the Chinese government before releasing personal information to entities outside China.

There is another source of AIS data available. Satellites passing overhead also receive AIS signals, roughly every 90 minutes. When ships are out of range of terrestrial AIS, then satellite AIS picks up the signal, providing valuable coverage in the high seas.

However, satellite AIS isn’t considered sufficiently accurate close to shore, so it’s not a perfect substitute for terrestrial AIS, certainly not for port monitoring.

What’s the bottom line? The last few weeks have taught everyone that relying solely on terrestrial AIS isn’t wise. Additional methods are necessary.

ursaspace.com

Author Geoffrey Craig is the Content Strategist, Ursa Space Systems, Inc.