2019 is the year of the smallsat... of course, 2018 was also the year of the smallsat... as was 2017 and 2016. Smallsat schedules always shift to the right — historically, there are several reasons for these occurrences.

Many companies pursuing smallsat applications are developing constellation strategies that consist of tens to thousands of satellites. The development of technology demonstrators and of full constellations requires substantial capital, often difficult to raise.

The year 2018 witnessed substantial movement on the financing front for constellation projects. Beyond the larger planned constellations such as OneWeb and Starlink that had previously announced funding, smaller constellations have also announced successful deployment of demonstration satellites and capital raises.

Cloud Constellation Corporation capped off 2018 funding announcements with a $100 million capital raise for space-based data centers, confirming there is venture capital interest for existing space-based applications as well as for unique applications that have not yet been implemented.

In all, closings of many hundreds of millions of dollars were announced for several new smallsat constellations in 2018 alone.

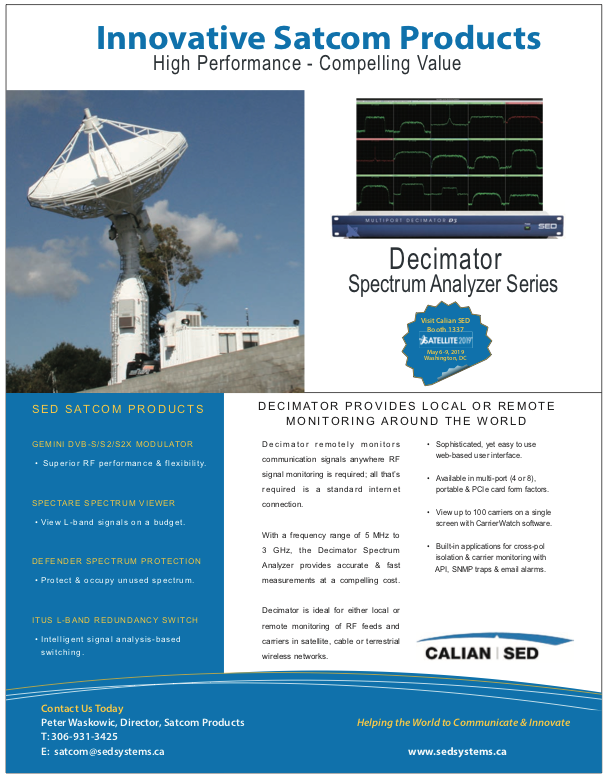

Artistic rendition of the Alpha separation. Image is courtesy

of Firefly.

In additional to financing, years of mission planning culminated in the successful December 2018 Spaceflight SSO-A mission; a pivotal milestone for the Smallsat industry.

With more than 35 companies participating, including firms such as Astro Digital, Astrocast, Audacy, Blacksky, Capella, Fleet Space, Hawkeye 360, ICEYE, Novawurks, Planet and Swarm, many companies were able to prove critical technologies, add to existing networks and, in some cases, trigger that always crucial, additional financing.

A primary concern involved in funding such disruptive endeavors expresses to new entrants in the smallsat industry is that these companies must — aside from proving their technology — must also show a viable path to space. A completely developed and manufactured smallsat sitting on a shelf collects dust and does not generate revenue.

As most smallsat constellations in development are in the under 300 kg. category, they are typically relegated to secondary payloads on large launch vehicles. Schedule and orbit are determined by the primary cargo and slips in the primary cargo schedule can have devastating effects.

A company that raises money to launch a technology demonstrator where additional funding will be released after the technology is proven would be exposed to substantial risk should the primary payload fall six months to a year behind schedule, as often happens with large satellite development efforts.

Companies with smallsat business cases must demonstrate access to economical and affordable launch services.

As of last year, a Northrop Grumman survey indicated there are more than 100 companies developing small launch vehicles to service the smallsat market.

Most of those companies are not expected to succeed, as the technical and financial hurdles smallsat launchers must overcome provide an extremely high barrier to entry.

Despite those barriers, the expectation is that several of the well-financed smallsat launcher companies will succeed and provide launch services to the burgeoning smallsat industry.

Pictured: Left, FIrefly’s Alpha launch vehicle — Right, Firefly’s Beta launch vehicle. Images are courtesy of the company.

Rocket Lab successfully executed three launches in 2018. Virgin Orbit has indicated they are preparing for their first launch in early 2019 and several other companies, including Firefly Aerospace, have announced an intention for an initial launch in 2019. Once the small launchers demonstrate consistent cadence at an economical price, additional smallsat business cases will begin to close and an even more rapid expansion of viable smallsat businesses will occur.

The Firefly Aerospace vehicle family is a primary path for this acceleration of the smallsat industry.

The company’s Firefly Alpha launch vehicle will accommodate 1,000 kg. of payload to a 200 km. Low Earth Orbit (LEO) and 630 kg. of payload to a 500 km. Sun Synchronous Orbit (SSO). The SSO orbit is widely regarded as a critical destination for smallsat Earth Observation (EO) platforms and is currently underserved by dedicated launches.

Firefly’s Alpha is the largest U.S. smallsat launch vehicle that is expected to be in service by the close of 2019 — no competing vehicles of a similar payload capacity are expected to be in service until at least 2021.

Surveys of potential customers have indicated the one metric ton capacity of the Alpha is in the “Goldilocks” range of dedicated smallsat launchers. The Alpha is large enough to deploy multiple 125 kg. class satellites so that planes of smallsat constellations can be

easily deployed while being small enough that aggregators can manifest entire vehicles consisting of a combination smallsats that could include microsatellites and CubeSats.

Firefly launch vehicle family will be expanded by adding the Beta vehicle by mid-2021. Beta is a four metric ton launch vehicle representing the only domestically available “Constellation Class” smallsat launcher and will directly compete with the with the Indian Space Research Organisation’s PSLV in both price and payload capacity.

Integrated stage test 3. Image is courtesy of Firefly.

Beta will be heavily derived from flight heritage Alpha technology, using substantially the same engines, structures and avionics. This will allow for rapid development of the Beta vehicle once the Alpha successfully launches and confirms performance and environment envelopes.

Beta will also allow for missions beyond LEO. Firefly was recently selected by NASA as one of nine companies competing to deliver science payloads to the surface of the moon. NASA expects to spend more than $2.6 billion dollars over the next decade on commercial lunar payload science missions.

By providing an integrated offering that includes a launch vehicle and lunar lander, Firefly will allow companies developing lunar payloads schedule assurance and reliable access to launch slots, which may rapidly accelerate the nascent lunar science industry.

Artistic rendition of the Beta separation. Image is courtesy

of Firefly.

Firefly has demonstrated schedule credibility by consistently hitting major development milestones.

Commencing stage qualification testing was one of Firefly’s primary goals for 2018 and was successfully achieved, demonstrating flight-configuration propulsion, structures and tankage, pressurization and propellant management systems, and avionics.

The stage operated autonomously, controlled by Firefly-developed flight software.

These tests also demonstrated full activation of Firefly’s large-scale vertical test stand, “TS2”, at Firefly’s Briggs, Texas test facility. In 2019, Firefly will continue qualification testing of both the first and second stages of Alpha and will begin flight acceptance testing in May, supporting a goal of a December 2019 first launch from Vandenberg Air Force Base Space Launch Complex 2-West.

Firefly rocket engine test. Image is courtesy of the company.

There truly is a new “Space Race” underway. While consolidation is expected, and some entrants in both the smallsat manufacturer and launcher verticals may not make it to the finish line, there is substantial room in the market for multiple winners in both verticals and exciting prospects ahead in 2019 and beyond.

firefly.com

Thomas E. Markusic is the founder and chief executive officer of Firefly. Prior to co–founding the comp[any, Tom served in a variety of technical and leadership roles in new-space companies: Vice President of Propulsion at Virgin Galactic, Senior Systems Engineer at Blue Origin, Director of the Texas Test Site and Principal Propulsion Engineer at SpaceX.

Prior to his new–space work, Tom was a civil servant at NASA and the USAF, where he worked as research scientist and propulsion engineer. He holds a Ph.D. in Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering from Princeton University.