Guido Baraglia, Board member of the Satellite Interference Reduction Group (IRG), discussed the current state of interference and the latest initiatives with SatMagazine. Mr. Baraglia, the Director at SAT Corp. (a KRATOS company), is a leading expert in Carrier Monitoring and Interference Geolocation, with more than 20 years of experience in combating RFI affecting telecommunication satellites. He’s participated on panels at SAT 2013, CabSat 2013, the WBU-ISOG conference in Geneva, ITU workshops and is a referenced source on RFI mitigation.

SatMagazine (SM)

As a member of SIRG who’s been intimately involved in interference reduction efforts, what’s the outlook on satellite interference and measures to reduce and counter it?

Guido Baraglia

I wish we could say interference is a thing of the past like the horse and buggy, but we’re facing several trends that all conspire to potentially create more problems. We’re seeing an exponential increase in satellite usage. We have almost 50 percent more satellites being built for launch from 2011-2020 than the previous decade, and capacity is doubling with the deployment of more High Throughput Satellites. Use isn’t limited to one sector, such as Direct-to-Home (DTH) television; there’s also remarkable uptake in business communications, Internet service, the Oil & Gas industry, stock exchanges, broadcast as well as mobile telephony.

On top of more bandwidth and services, there’s also a lower barrier to entry. Smaller and smaller VSAT terminals are sprouting up, particularly for the new generation of DTH Internet terminals operating in Ka-Band. Where we had fewer, but more experienced installers, we now have, more often than what we might realize, technicians with little to no experience in installing satellite terminals. This situation applies to nearly all verticals. Without proper skills, there are more problems originating from installation faults than ever before. Budget and cost pressures are often squeezing out basic elements such as equipment maintenance and staff training.

We’re also seeing some technical innovations, such as the all-electric satellites. It’s a promising “green” concept, but it will create issues for the techniques and algorithms everyone uses for geolocation.

The upside of is that the vast majority of interference is unintentional—there’s more corrective actions we can take to mitigate it. The sunny, optimistic answer is that the satellite industry is positioned for exceptional growth. The cloudier side is that more capacity, users, and services will create more interference challenges.

SM

Given that prognosis, what are some of the promising international initiatives and recommendations?

Guido Baraglia

There are several industry answers, including Carrier ID, Operators’ Training, and Type Approval to mitigate the effect of interferences on daily satellite operations. One of the more far-reaching and promising relates to the International Telecommunications Union suggestion that each individual administration controls its own spectrum, with nations setting up their own International Monitoring Stations (IMS). These would be equipped with monitoring and geolocation tools, which are the assets that provide detection, characterization and, most of the time, resolution of interference problems.

Considering the patchwork of satellite activity, the rationale to have an umbrella entity for a national territory makes a lot of sense. Nearly everyone has skin in the game so to speak; the satellite operators, service providers, national governments, manufacturers, the international community…we’re all in this together. These international monitoring stations can operate as independent third parties to validate RF activity, and monitor and geolocate sources of interference.

Radio Space Frequency Spectrum is simply becoming more crowded, with too little orbital positions, frequencies and coverage regions for everyone who wants to own a telecommunication satellite. Obviously the ITU, as the regulatory body of all spectrum activity, has thought long and hard about how we’ll all coexist.

SM

Is there a model for these international monitoring stations, and what would these look like?

Guido Baraglia

These installations have the ability to monitor, record and detect transmissions from any space station, the ITU convention for orbiting satellites transmitting towards Earth. And some of them also have the ability to precisely geolocate the source of any transmission, independently, whether it’s legitimate or not.

There are two possible approaches to the International Monitoring Station, a scientific approach whereas the authority wants to receive and monitor all possible signals that come from space stations, independent of their origin, usage and orbit. This model requires considerable investments and highly trained engineers for the day-to-day operations and data analysis.

The second model is a more commercial approach to the signal monitoring and limits the scope of the monitoring station to commercial geostationary services and specific frequency bands only.

A scientific approach will allow the authority to receive signals transmitted from all types of satellites and for all types of services, including GPS, weather satellites, Earth observation satellites and so on. It will also allow monitoring of non-geostationary orbit spacecraft. Given the current usage of the satellite spectrum, the commercial approach will, nonetheless, allow the authority to monitor approximately 90 percent of the signals received from orbiting objects.

Essentially, an International Monitoring Station will look like just another teleport and to a certain extent, it is. Also, the tools used to monitor and geolocate signals would be common to most commercial teleport or satellite operators. What will change are the requirements for accuracy and repeatability of the measurements performed by an IMS.

Deciding which type of satellite, service and frequency band to monitor will help determine the required budget.

SM

Why would a country want to set up an IMS? Aren’t their carriers or service providers doing that? What would be the benefit?

Guido Baraglia

Suppose commercial entity ‘A’ in one nation is having an interference issue with ‘B’ in another nation. Despite best intentions, it will be one word against the other. Clearly, there are advantages of having a 3rd party organization, possibly under the ITU umbrella, that’s capable of detecting, characterizing, and eventually geolocating, the said anomaly and presenting the case to the international community. An authority recognized by the ITU that sits above external interests carries more credibility and weight and can more effectively and easily resolve disputes between countries or different entities whatever the disruption, service, or frequency dispute.

The aim for the ITU will be to build a bigger network of coordinated ground stations to verify and measure each anomaly in an unbiased way.

There’s also the benefit of being able to monitor which entities can transmit over the national territory. There may be groups transmitting or setting up a network without proper authorization, or not following the basic rules to avoid interfering with other services or satellite networks. Using a mix of fixed and mobile ground stations, the regulatory authority can control most, if not all, of the traffic over the national territory, verifying not only what lands in the territory, but also the signals transmitted from within the national territories.

SM

Would international monitoring stations also play a role in national security matters?

Guido Baraglia

Yes, they certainly would. They can monitor and detect possible threats, whether that’s deliberate jamming or unauthorized satellite use, and help verify the source of content that might be considered a threat.

While deliberate interference is obviously a small portion, only three to four percent, we’ve seen a lot more activity emanating from the Middle East in the past several years. Of course, deliberate interferences or denial of service have occurred since Captain Midnight in the late 1980’s, but as a political tool, deliberate interference will continue to be used in this region, unless proper actions are taken by the competent authorities.

Also, if a nation has its own space program or satellite in orbit, an international monitoring station can help control and police the assets in space, protecting bandwidth and avoiding attempts to deny service if necessary. This becomes particularly important for nations that are about to enter a space program and have to contest for an available orbital slot against real and “paper” satellites.

SM

Which nations are currently doing this?

Guido Baraglia

According to the ITU Report SM.2182 there are seven International Monitoring Stations in the world: the U.S., Germany, Korea, China, Ukraine, Kazakhstan and Japan. An eighth one in being deployed by Russia, but hasn’t yet made it to the ITU Report. The German installation is, in reality, the result of a MoU between seven European nations who are members of the CEPT—they are Germany, France, UK, Switzerland, Spain, Luxembourg and The Netherlands. This installation is operated by the German Authority on behalf of the MoU members,

SM

What challenges or hurdles are you hearing from the frequencies regulators?

Guido Baraglia

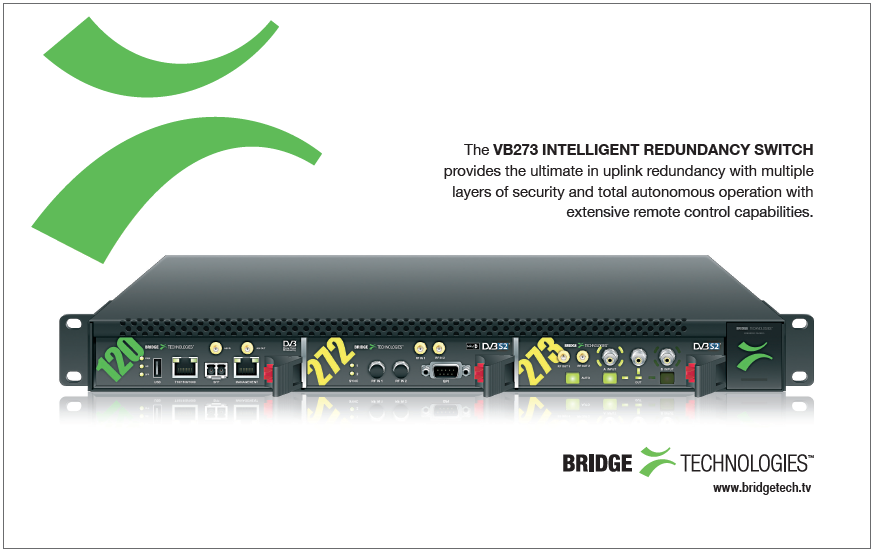

The long held perception is that the hardware and software for monitoring and geolocation of space radio services are too specialized and too expensive. Frequency regulators, however, can use the same widely available commercial equipment as that used by satellite operators or broadcasters. There’s no difference in the tools, procedures or training between the commercial and the regulator way of monitoring. If private companies can afford it, so too can the frequency regulator authority.

Eventually a certain degree of cooperation can be envisioned between commercial entities and regulators, where if you have a service provider with a teleport, the authority could use that as the structure for the international monitoring station.

Another concern from the past has been how to staff these operations with the specialized expertise. However, today’s tools and technologies having changed so much, that’s not as big an issue anymore. A Level 1 operator today can now take on far more of the monitoring to mitigation cycle, rather than being limited to a small piece of the problem and escalating it up. Toolsets for detection and geolocation can be integrated together with a much higher degree of automation. You can pull data from monitoring, such as detailed signal-under-signal characterization, into a graphical interface for more complete analysis and geolocation. Staff can then do more than detect a problem; they can take the next steps to locate and resolve it. Bridges between the authority service database and the monitoring tools are more and more common.

Other advances, like map-based tools, make it easier to understand today’s complex satellites’ scenarios that involve more beams, switching, and transponders. A lot of your readers may not remember the old DOS-based computers before the graphical interface came along, but that was typical of the equipment. Now with today’s intuitive displays, operators can more easily interpret and interact with the information. Using an interface where the data is overlaid and visualized on a detailed map greatly speeds up the geolocation and mitigation process.

SM

Are you optimistic?

Guido Baraglia

Absolutely. If each nation took part and implemented the International Monitoring Station concept, where they’re actively monitoring the radio space frequency spectrum, then all parties would benefit from equal rights access and the use of it.

For further information regarding IRG: http://satirg.org