I just finished reading a LinkedIn article that listed three points to consider when contemplating SATCOM as a career path. While the points did have merit, I couldn’t help but flash back to the way things were long ago and ponder the contrast between what new entrants face nowadays and what we faced back then.

When I came to the party in the ‘70s, there were very few players in the industry—if you could even call it an industry. Since commercial applications were virtually non-existent, the term ‘satellite’ was far from being the household word that it is today.

The big three TV Networks were still taping their programs and sending them to their affiliate stations via UPS, cable TV was in its infancy and a home-sat terminal that was only available from the Nieman-Marcus catalog would set you back $10,000.

Entertainment programming was limited to RCA’s SATCOM-1 satellite, which carried 24 C-band transponders, each capable of transmitting a single analog TV channel. SATCOM-II was in service, but it was dedicated to specialty programming, such as beaming I Love Lucy and The Andy Griffith Show to our troops deployed overseas.

The limited availability of transponders meant that the growth potential for the broadcast-via-satellite market would be unrecognizable unless something changed.

I’ll never forget the day RCA announced they were launching SATCOM-III that, like SATCOM-I, would be dedicated to the transmission of entertainment programming for cable TV operators.

I was working for Scientific Atlanta’s CATV Division at the time and that announcement caused the demand for our products to literally explode.

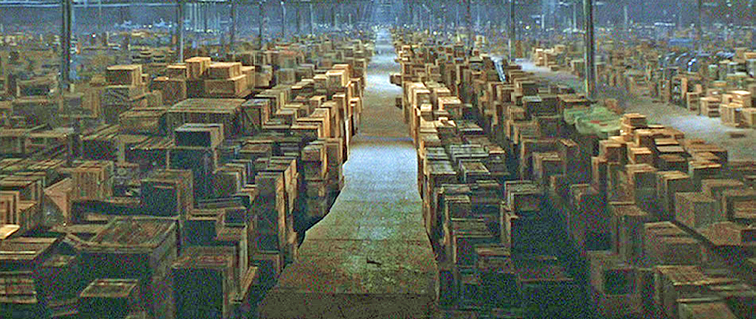

We had to put on two additional shifts just to handle the flood of orders for the antennas and head-end equipment they would need to take advantage of the new bird. Our ‘Finished Goods’ stockroom looked like the final scene in Raiders of the Lost Arc.

Unfortunately, the celebration was short lived, for amidst rabid anticipation, SATCOM III slipped into an elliptical orbit and never made it to its dedicated parking spot. Instead, the spectacular ‘clean-room contrivance’ that embodied the hopes and dreams of a fledgling industry became nothing more than space debris. Needless to say, the commensurate flood of order cancellations left us with two years worth of inventory and prompted the firm’s reversion to a single-shift operation.

After a tepid lull of industrial stagnation, SATCOM III-R was successfully placed into service. That was followed by a rash of successive launches that were sorely needed to quench the demand for broadcast towers that were 22,000 miles tall.

In no time at all, we were shipping more than $1 billion in CATV products, much to the delight of a nationwide pool of anxiously awaiting couch potatoes.

I consider the 1980s to be the Renaissance Era of satellite communications. It was during the ‘80s that the market really seemed to take off. I was traveling 300 days out of the year building Earth stations everywhere. NBC, CBS and ABC simultaneously launched corporate-wide satellite networks to replace the brown trucks.

Super stations, sports networks, 24-hour news and ‘round the clock’ movies became readily available to millions of city dwellers. Hotels and apartment complexes across the country were wired for satellite.

Rabbit ears with little aluminum-foil bow-ties were replaced with set top converters and the hours previously dedicated to societal past times such as camping, fishing and neighborhood sports would now be logged as seat time on couches and recliners by a burgeoning audience, hungry for effortless entertainment.

Soon, inexpensive home systems came to the market—ensuring that even those who existed beyond the reach of cable distribution could join the ranks of sedentary spectators.

What a fantastic period it was for us Earth station antenna aficionados who reveled in the mystique of this new technology. The spectacle of SATCOM was alien to the average Joe—exacerbated by the fact that satellites of the day had weak footprints.

This meant that dishes had to be huge and complex (at least by today’s standards). They struggled to grasp the idea that a giant bowl could somehow collect television signals from an electronic gizmo suspended tens of thousands of miles out into space—black magic and we were the wizards of conveyance.

The rapid growth in demand for satellites as a means for content distribution drove the need for additional launches to the point that birds were being parked right next to each other. This placed a major burden on antenna manufacturers as the signal beams between the Earth stations and the satellites had to be narrowed so as to hit only one satellite at a time. Techniques used in antenna manufacturing required a complete overhaul.

Even with satellites parked within two degrees of each other, the demand for transponders continued to outstrip capacity. It became necessary to transcend the boundaries of C-band and use other portions of the frequency spectrum—out came the slide rules and Ku-band became the next roadmap destination for pretty much every SATCOM product manufacturer.

Of course, all of that additional spectrum came at a price. Dishes had to be even smoother to work at Ku-band, so a theodolite had to be added to our tool kits to precisely align the reflector panels. Narrower beams brought the need for higher tracking accuracy.

And then the rains came. Uplink Power Control and waveguide dehydrators became critical components of Earth station architecture.

About the time frequency issues were squared away and things seemed to settle down, the ‘digital transformation’ arrived. Analog video exciters became digital modulators, S/N was replaced with Eb/No, multiplexers turned SCPC into MCPC and bandwidth utilization became the predominant goal for manufacturers and users alike.

With each new launch, satellites were becoming more powerful and more sensitive, so dishes started shrinking. Big concrete foundations were replaced with pipe mounts installed with a pair of post-hole diggers and a bag of Sakrete. What used to take industrial cranes, rigging and safety belts now could be done with a half-inch wrench and a screwdriver. It was awful.

But, again—we adapted. As technology changed all around us and imposed its intrusive grip on an industry that’s so dependent upon ‘spectral efficiency,’ we reinvented ourselves accordingly.

Our products evolved. TWTAs became SSPAs and LNAs became LNBs. Elliptiguide, once the backbone of every satellite uplink, was removed, stripped of it’s insulation, melted down and fashioned into cookware and those little bracelets that cure arthritis—only to be replaced with cheap coax that you could purchase from Radio Shack.

A few more years would pass before we were hit with another technological tidal wave that injected itself into the process—this went by the name of ‘Internet Protocol.’ In short order, the migration from a dozen different interfaces to a common standard would ensue. Old school veterans that were masters of RS 250C had to make way for the packet-hacks that were Cisco-certified.

The trials and tribulations that face the SATCOM newbies of today have taken a totally different form. Back then, newbies didn’t even know what SATCOM was until they were already in too deep.

The only folks you could ask for direction wore thick glasses and pocket protectors. Even if you could get them to talk, they were hard to understand.

It was a world of black magic—coarse and crude, yet complex and precise. ‘Standards’ were few and many trails were yet to be blazed.

Fast forward 35 years. The SATCOM of today is far different. There are ‘standards’ for everything. Components are smaller and lighter. Most of the installation work is done indoors—not out on the pad. Heavy test instruments have been replaced with hand-held monitors and iPhone apps. Today, you can use the same tools to build an Earth station that you used to assemble your kid’s bike.

Perhaps the most impactful ontogeny was the adoption of IP as a common transport medium for virtually all forms of content, whether it be voice, video or data. The fact that each of these forms had to be handled differently was a major source of the complexity and commensurate challenge imposed on the pioneers of satellite communications.

Today, the SATCOM Industry is more civilized and sophisticated, not unlike any other trade within the telecommunications domain. Still, there are a few trails left to blaze. The challenges imposed by the new LEO and MEO platforms will keep the SATCOM community on its toes for a while and Ka-band will give way to Q-band as the hunger for space-based services grows. After all, there are still a few billion who haven’t yet signed up for LinkedIn or Facebook.

Having spent most of my life here, I can’t say that SATCOM is a bad place to be, but I can say that it’s nothing like it was back in the good old days.

Tony Radford, a 38 year veteran of the Satellite Communications Industry, has served as VP Sales & Marketing for Paradise Datacom since 2004.

Tony’s book, “Satcom Guide for the Technically Challenged,” is available at: https://www.amazon.com/Satcom-Guide-Technically-Challenged-Radford/dp/0966545133/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1486639504&sr=8-1&keywords=satcom+guide+for+the+technically+challenged