About 100 years ago, Hungarian poet Frigyes Karinthy and English writer G. K. Chesterton invented the “Chain-Link Game” with a group of close friends1.

The rules of the game were simple. One player would identify any two people in the world, and the other players would compete to see who could construct the shortest linkage between those two people through a network of individuals, each of whom should know the next one through a shared experience.

No matter how long they played, or how distantly removed one person was from the other, the friends never needed more than six links to connect the chain.

From this early-20th-century parlor game arose the college drinking game “Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon2” and the small-world phenomenon of six degrees of separation.

Coincidentally, just a few years earlier in 1909, Italian inventor Guglielmo Marconi had estimated he could link the globe with a network of only six wireless telegraph radio repeater stations3.

Decades later in 1967, American sociologist Stanley Milgram showed that on average it takes only about six links to relay a letter from any randomly selected individual to any random recipient — given that each intermediary was told to forward the letter to the person he or she personally knew who was most likely to know the recipient4.

In 2008, researchers at Microsoft found that 80 percent of the 180 million Microsoft Messenger users at the time could be connected by six or fewer personal links5.

Paradoxically, while the world’s population has exploded to 8 billion people, each of us has become closer to one another than ever before. As explained by Karinthy and Chesterton:

“Julius Caesar, for instance, was a popular man, but if he had got it into his head to try and contact a priest from one of the Mayan or Aztec tribes that lived in the Americas at that time, he could not have succeeded — not in five steps, not even in three hundred. Europeans in those days knew less about America and its inhabitants than we now know about Mars and its inhabitants.”

One hundred thousand years ago, on the windswept plains of sub-Saharan Africa, Homo sapiens emerged with the uniquely human desire for prosperity and a better future. Those passions launched our species on multiple divergent paths of nomadic exploration and colonization, which have now fully encircled our planet.

Now, the Space Age has given all the technological means for instantaneous global communication and, with those capabilities, the means to connect as one global tribe in a way that has not been possible for 100,000 years. This has created the small-world phenomenon of six degrees

of separation.

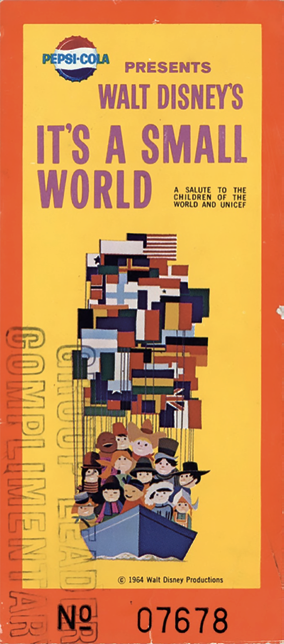

At the start of the Space Age, the City of New York hosted the 1964 World’s Fair that enveloped the theme of Global Peace Through Understanding and showcased Space Age technological advancements that were shrinking the globe, all the while expanding Homo sapiens connection with the universe.

With sponsorship from Pepsi-Cola and as a salute to the children of the Space Age, Walt Disney debuted an interactive exhibit at the fair with animated children frolicking in miniature settings from many lands. The fanciful creation of multi-cultural imagery sent a message of peace and brotherhood harmonized by a soundtrack entitled “It’s a Small World (After All)6.”

Those children have now become the leaders of today’s space industry and they are re-inventing the industry’s mid-20th Century values and visions with a fresh focus on the human elements of the space business, such as work-life balance, cultural diversity and the importance of the social network.

New space magnates like Jeff Bezos, Greg Wyler, Elon Musk, and Richard Branson are pouring $billions into small-world business ventures such as global internet and space tourism that will help people to stay even more connected to one another.

What does this mean for all humankind?

Personal differences aside, we all hunger to be a part of the Space Age. I don’t think it’s just because we think rocket science is cool. I think it is because only six Homo sapiens separate us from each of the 8 billion others in the world — somehow space helps us feel the goodness in the 100,000-year-old tribal connection we have with one another.

www.roccor.com

References

1Frigyes Karinthy, “Chain-Links,” 1929

2www.sixdegrees.org

3Guglielmo Marconi, “Wireless telegraphic communication,” Nobel Prize Acceptance Lecture, December 11, 1909

4Stanley Milgram, “The Small World Problem”. Psychology Today, May 1967. Ziff-Davis Publishing Company.

5Peter Whoriskey, “Instant Messagers Really Are About Six Degrees from Kevin Bacon; Big Microsoft Study Supports Small World Theory,” The Washington Post, Aug 2, 2008

6Dave Smith, Disney A to Z: The Official Disney Encyclopedia, 2006

Mark Lake is Vice President of R&D at Roccor where he oversees technology and advanced product development efforts, multi-organization cooperative ventures and strategic partnerships for technology capitalization.

Roccor is an aerospace supplier providing low-cost, high performance deployable structure and thermal management systems technology for government and commercial space customers.

Dr. Lake started his career as a research engineer and program manager for NASA. He has published more than 50 research publications in the field of aircraft and spacecraft structures and a book entitled, The Inventor’s Puzzle: Deciphering the Business of Product Innovation. He is also an Associate Fellow of the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics and an adjunct member of the graduate faculty of the department of Aerospace Engineering Sciences at the University of Colorado.